By KATH GANNAWAY

IT MAY seem cliched, but Captain George Ingram proved himself to be a leader of men.

There are plenty of stories of leaders leading from behind on the battlefields of WWI, but history records that Yarra Ranges’ only WWI Victoria Cross recipient, never asked his men to do anything he wasn’t prepared to do himself.

He was six when the family moved to Seville, where his father was a mail contractor and orchardist.

An older brother, Ronald, and younger brother, Alex, would be killed in the war. He also lost a sister when she was just six.

A troubled teenager, he left school at 14 and after a scrape with the law, was sent to live in Prahran where he got an apprenticeship as a carpenter.

At the same time, he joined the militia.

Those formative years underpinned a life which by today’s standards, or perhaps the standards of any era, would rate as heroic.

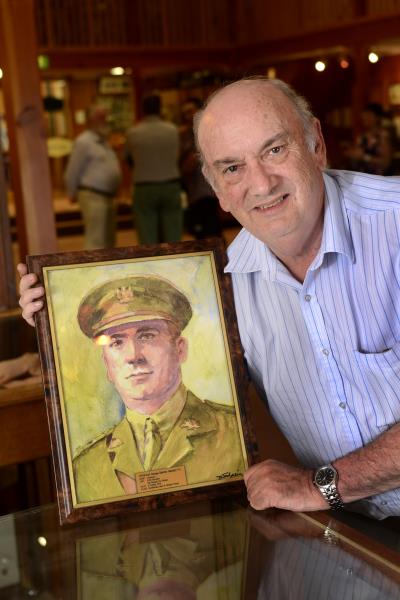

That’s reflected in Mt Evelyn military historian, Anthony McAleer’s book ‘Great Courage and Initiative’ – The Heroic Life of George Ingram VC, MM.

The biography, launched in March, was sparked by a desire, and need, to tell the story.

“Australians, although we’re a very egalitarian society, always hold our VC recipients on a pedestal,” McAleer said.

“I wanted to do the book to create the interest, but the real story is what those fellows had to go through on the Western Front and how they suffered because of their service after the war,” he said.

He was awarded the Military Medal for his role during the first action on the front line at Bapaume.

Over the next two years, McAleer says, he experienced all the horror and heroism of the Western Front.

He survived the killing grounds of Bullecourt, Ypres, Flanders, Passchendaele, Villers Bretonneux and Mont St Quentin.

It was his actions on 5 October, 1918, at Montbrehain, the AIF’s last battle of the war, that led to him earning the highest award for gallantry in battle.

A detailed description of the battle is covered in Wikipedia ‘George Ingram’, and it is compelling reading.

When the battalion came under heavy fire, Ingram rushed an enemy post and captured nine machine-guns, killing 42 of the enemy in the process.

Several more times throughout the day he displayed great courage, capturing posts and many more prisoners.

He was decorated with his Victoria Cross by King George V at Buckingham Palace on 25 February, 1919, before returning to Australia where he was discharged in June.

McAleer covers the after story, as much as in the heroic action on the battle field.

“For the rest of his life, Ingram never spoke about how he won the VC,” he said.

“It was traumatic; he was responsible for the death of more than 40 men on that day, hand to hand combat, and that’s going to haunt anyone.

“A lot of his good friends were killed on that day, and in the lead-up to that his two brothers had been killed.”

McAleer says George Ingram returned to a hero’s welcome at Seville, but suffered both mentally and physically right up to his death as a result of the injury and trauma of war.

He said it took him a long time to come to terms with the medal that represented all that.

“It (the VC) is very much about the individual, and they don’t want it to be about them,” he said.

“In time there can be an acceptance that it’s representative of more than the individual, but of all those who were there, and what they did.

“After that they can then go out and feel that they are representing the people who didn’t come back.”

In 1934 he became one of the original Shrine Guards, then went on to serve in WW2.

In 1956 he attended the Victoria Cross Centenary and while in Europe placed soil from Seville on the graves of his brothers.

George Ingram, VC, MM, died in 1961.

Commemorative gates at Seville Primary School mark his contribution to WWI as a ‘Seville boy’.